|

For Pilots and Flight Operations Personnel PART I. WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT WEATHER

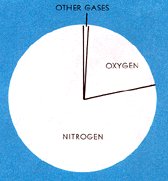

Planet Earth is unique in that its atmosphere sustains life as we know it. Weather - the state of the atmosphere - at any given time and place strongly influences our daily routine as well as our general life patterns. Virtually all of our activities are affected by weather, but of all man's endeavors, none is influenced more intimately by weather than aviation. Weather is complex and at times difficult to understand. Our restless atmosphere is almost constantly in motion as it strives reach equilibrium. These never ending air movements set up chain reactions which culminate in a continuing variety of weather. Later chapters in this book delve into the atmosphere in motion. This chapter looks briefly at our atmosphere in terms of its composition; vertical structure; the standard atmosphere; and of special concern to you, the pilot, density and hypoxia.

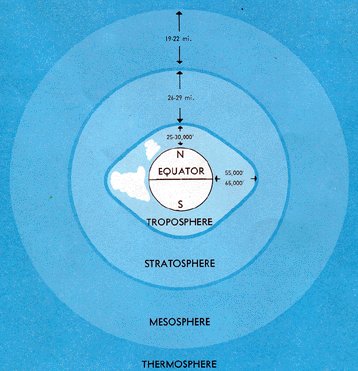

VERTICAL STRUCTURE

The TROPOSPHERE is the layer from the surface to an average altitude of about 7 miles. It is characterized by an overall decrease of temperature with increasing altitude. The height of the troposphere varies with latitude and seasons. It slopes from about 20,000 feet over the poles to about 65,000 feet over the Equator; and it is higher in summer than in winter. At the top of the troposphere is the TROPOPAUSE, a very thin layer marking the boundary between the troposphere and the layer above. The height of the tropopause and certain weather phenomena are related. Chapter 13 discusses in detail the significance of the tropopause to flight. Above the tropopause is the STRATOSPHERE. This layer is typified by relatively small changes in temperature with height except for a warming trend near the top.

The decrease in air density with increasing height has a physiological effect which we cannot ignore. The rate at which the lungs absorb oxygen depends on the partial pressure exerted by oxygen in the air. The atmosphere is about one-fifth oxygen, so the oxygen pressure is about one-fifth the total pressure at any given altitude. Normally, our lungs are accustomed to an oxygen pressure of about 3 pounds per square inch. But, since air pressure decreases as altitude increases, the oxygen pressure also decreases. A pilot continuously gaining altitude or making a prolonged flight at high altitude without supplemental oxygen will likely suffer from HYPOXIA - a deficiency of oxygen. The effects are a feeling of exhaustion; an impairment of vision and judgment; and finally, unconsciousness. Cases are known where a person lapsed into unconsciousness without realizing he was suffering the effects. When flying at or above 10,000 feet, force yourself to remain alert. Any feeling of drowsiness or undue fatigue may be from hypoxia. If you do not have oxygen, descend to a lower altitude. If fatigue or drowsiness continues after descent, it is caused by something other than hypoxia. A safe procedure is to use auxiliary oxygen during prolonged flights above 10,000 feet and for even short flights above 12,000 feet. Above about 40,000 feet, pressurization becomes essential.

|