|

For Pilots and Flight Operations Personnel PART I. WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT WEATHER

To a pilot, the stability of his aircraft is a vital concern. A stable aircraft, when disturbed from straight and level flight, returns by itself to a steady balanced flight. An unstable aircraft, when disturbed, continues to move away from a normal flight attitude. So it is with the atmosphere. A stable atmosphere resists any upward or downward displacement. An unstable atmosphere allows an upward or downward disturbance to grow into a vertical or convective current. This chapter first examines fundamental changes in upward and downward moving air and then relates stable and unstable air to clouds, weather, and flying.

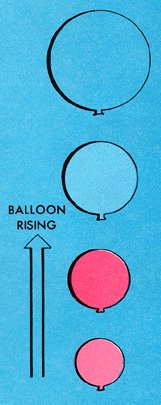

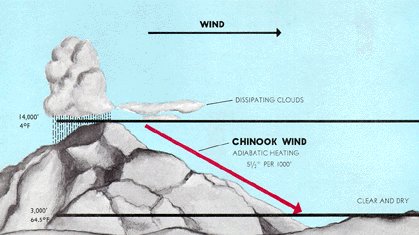

Unsaturated air moving upward and downward cools and warms at about 3.0° C (5.4° F) per 1,000 feet. This rate is the "dry adiabatic rate of temperature change" and is independent of the temperature of the mass of air through which the vertical movements occur. Figure 41 illustrates a " Chinook Wind" - an excellent example of dry adiabatic warming.

Condensation occurs when saturated air moves upward. Latent heat released through condensation (chapter 5) partially offsets the expansional cooling. Therefore, the saturated adiabatic rate of cooling is slower than the dry adiabatic rate. The saturated rate depends on saturation temperature or dew point of the air. Condensation of copious moisture in saturated warm air releases more latent heat to offset expansional cooling than does the scant moisture in saturated cold air. Therefore, the saturated adiabatic rate of cooling is less in warm air than in cold air. When saturated air moves downward, it heats at the same rate as it cools on ascent provided liquid water evaporates rapidly enough to maintain saturation. Minute water droplets evaporate at virtually this rate. Larger drops evaporate more slowly and complicate the moist adiabatic process in downward moving air. ADIABATIC COOLING AND VERTICAL AIR MOVEMENT If we force a sample of air upward into the atmosphere, we must consider two possibilities:

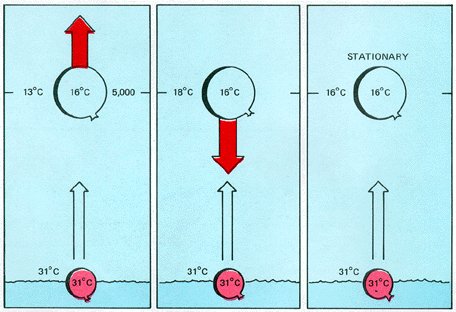

If the upward moving air becomes colder than surrounding air, it sinks; but if it remains warmer it is accelerated upward as a convective current. Whether it sinks or rises depends on the ambient or existing temperature lapse rate (chapter 2). Do not confuse existing lapse rate with adiabatic rates of cooling in vertically moving air.* The difference between the existing lapse rate of a given mass of air and the adiabatic rates of cooling in upward moving air determines if the air is stable or unstable. * Sometimes you will hear the dry and moist adiabatic rates of cooling called the dry adiabatic lapse rate and the moist adiabatic lapse rate. In this book, lapse rate refers exclusively to the existing, or actual, decrease of temperature with height in a real atmosphere. The dry or moist adiabatic lapse rate signifies a prescribed rate of expansional cooling or compressional heating. An adiabatic lapse rate becomes real only when it becomes a condition brought about by vertically moving air.

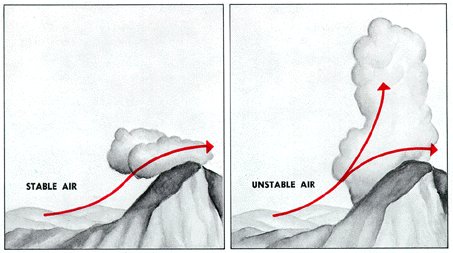

In situation two (center) the air aloft is warmer. Air inside the balloon, cooling adiabatically, now becomes colder than the surrounding air. The balloon sinks under its own weight returning to its original position when the lifting force is removed. The air is stable, and spontaneous convection is impossible. In the last situation, temperature of air inside the balloon is the same as that of surrounding air. The balloon will remain at rest. This condition is neutrally stable; that is, the air is neither stable nor unstable. Note that, in all three situations, temperature of air in the expanding balloon cooled at a fixed rate. The differences in the three conditions depend, therefore, on the temperature differences between the surface and 5,000 feet, that is, on the ambient lapse rates. HOW STABLE OR UNSTABLE? Stability runs the gamut from absolutely stable to absolutely unstable, and the atmosphere usually is in a delicate balance somewhere in between. A change in ambient temperature lapse rate of an air mass can tip this balance. For example, surface heating or cooling aloft can make the air more unstable; on the other hand, surface cooling or warming aloft often tips the balance toward greater stability. Air may be stable or unstable in layers. A stable layer may overlie and cap unstable air; or, conversely, air near the surface may be stable with unstable layers above. Chapter 5 states that when air is cooling and first becomes saturated, condensation or sublimation begins to form clouds. Chapter 7 explains cloud types and their significance as "signposts in the sky." Whether the air is stable or unstable within a layer largely determines cloud structure. Stratiform Clouds Since stable air resists convection, clouds in stable air form in horizontal, sheet-like layers or "strata." Thus, within a stable layer, clouds are stratiform. Adiabatic cooling may be by upslope flow as illustrated in figure 43; by lifting over cold, more dense air; or by converging winds. Cooling by an underlying cold surface is a stabilizing process and may produce fog. If clouds are to remain stratiform, the layer must remain stable after condensation occurs.

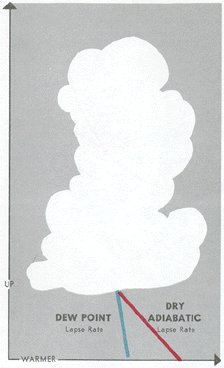

Unstable air favors convection. A "cumulus" cloud, meaning " heap," forms in a convective updraft and builds upward, also shown in figure 43. Thus, within an unstable layer, clouds are cumuliform; and the vertical extent of the cloud depends on the depth of the unstable layer. Initial lifting to trigger a cumuliform cloud may be the same as that for lifting stable air. In addition, convection may be set off by surface heating (chapter 4). Air may be unstable or slightly stable before condensation occurs; but for convective cumuliform clouds to develop, it must be unstable after saturation. Cooling in the updraft is now at the slower moist adiabatic rate because of the release of latent heat of condensation. Temperature in the saturated updraft is warmer than ambient temperature, and convection is spontaneous. Updrafts accelerate until temperature within the cloud cools below the ambient temperature. This condition occurs where the unstable layer is capped by a stable layer often marked by a temperature inversion. Vertical heights range from the shallow fair weather cumulus to the giant thunderstorm cumulonimbus - the ultimate in atmospheric instability capped by the tropopause. You can estimate height of cumuliform cloud bases using surface temperature - dew point spread. Unsaturated air in a convective current cools at about 5.4° F (3.0° C) per 1,000 feet; dew point decreases at about 1° F (5/9° C). Thus, in a convective current, temperature and dew point converge at about 4.4° F (2.5° C) per 1,000 feet as illustrated in figure 44. We can get a quick estimate of a convective cloud base in thousands of feet by rounding these values and dividing into the spread or by multiplying the spread by their reciprocals. When using Fahrenheit, divide by 4 or multiply by 0.25; when using Celsius, divide by 2.2 or multiply by 0.45. This method of estimating is reliable only with instability clouds and during the warmer part of the day.

Merging Stratiform and Cumuliform A layer of stratiform clouds may sometimes form in a mildly stable layer while a few ambitious convective clouds penetrate the layer thus merging stratiform with cumuliform. Convective clouds may be almost or entirely embedded in a massive stratiform layer and pose an unseen threat to instrument flight.

1. Thunderstorms are sure signs of violently unstable air. Give these storms a wide berth.

|